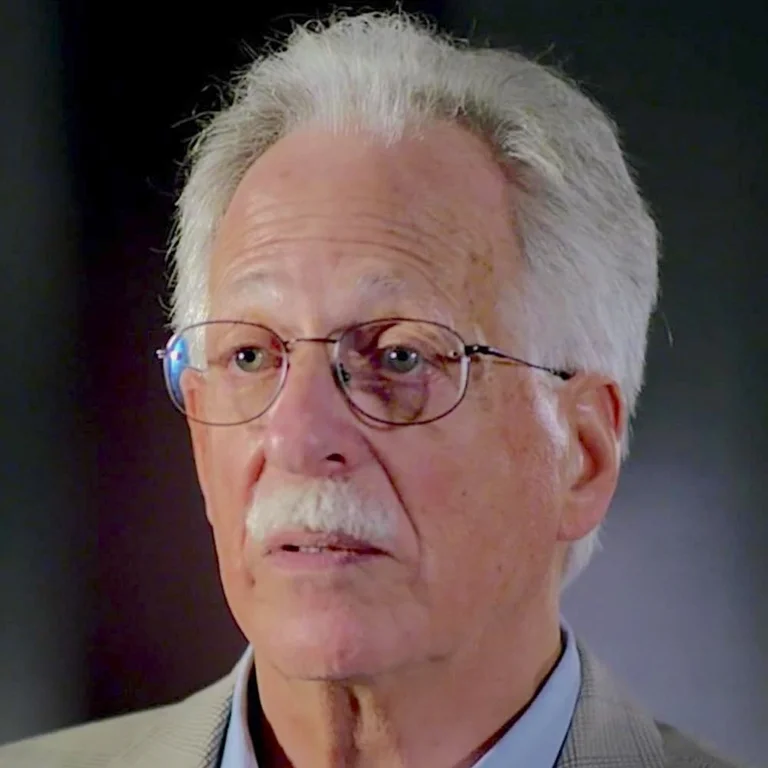

PEOPLE TO WATCH 2014: Rob Goldstein

For Rob Goldstein, the decision to join Las Vegas Sands, the company operated by Sheldon Adelson, was one he never regrets.

“Are there ups and downs?” he asks. “Sure, anytime you have a wide-eyed entrepreneur and visionary guy like Sheldon that’s going to happen. But I could not have asked for a better situation and results. When you think about the impact we’ve had in Las Vegas, Macau and Singapore, I’m very grateful. It’s far beyond anything I could ever hope for. I’ve had to adapt and be on my toes at all times, but overall, it’s been terrific.”

Doubts always surrounded the seemingly outrageous plans laid out by Adelson, from the focus on meetings and conventions in Las Vegas, to the visualization of Macau’s Cotai, to the construction of an iconic building in Singapore, but he rarely fails to produce results.

“Every place he’s gone, there have been naysayers,” says Goldstein. “And every place he’s gone, he’s nailed it.”

For Goldstein, Adelson’s big contribution to gaming has been the growth of non-gaming amenities, particularly in Asia.

“When you look at Sheldon in the aggregate,” he explains, “Macau might be the single-most fascinating decision because it not only helped LVS; it also helped our competitors. There was tremendous scorn and ridicule when he announced what he planned to do, but if he hadn’t pushed forward with this, you wouldn’t have what we see in Macau today. He authored the idea of Cotai with these non-gaming-centric buildings, with retail, spas, meetings and conventions, superstar sports and entertainment and all the other amenities. That couldn’t have happened in the old Macau.

“So you have to look at him in a different light and consider the impact he’s had on people’s lives in Vegas and in Asia.”

The explosive growth of the revenue in Macau will continue to increase, says Goldstein.

“I think Macau will be the world’s first $100 billion gaming market,” he says. “I like to say all gaming is local, and the glory of Macau is that its local market is called China. The junket business drove it in the early days, but increasingly it’s becoming the mass market that is growing quickly.

“I don’t see any end to it, because if the high-speed rail and all the infrastructure improvements to get more people to visit Macau than the government is making happen, I don’t see how it doesn’t continue to boom.”

Even with at least five new integrated resorts currently under construction in Cotai, Goldstein barely sees a blip on the market share.

“Everyone has figured it out,” he says. “You have to take your hat off to Melco Crown and Galaxy. They have become the drivers on Cotai. When Steve Wynn opened the Encore in Macau, that was the first time that people realized the size of the premium mass market, as it’s called.

“I don’t think the market will grow that quickly when all the resorts open, but it won’t take long because on a parallel track you’ve got the airport, the rail system, bridge from Hong Kong and border crossings expanding.”

Goldstein isn’t so enthusiastic about Las Vegas, although he calls it home.

“I’ve been living in Vegas for 18 years with my family,” he says. “We love it, but I’m worried about the future. The core customer of Las Vegas is middle America that was impacted significantly by the financial downturn of five years ago. That was the more affluent, high-end customer. It’s going to take a while for that customer to come back to Las Vegas and spend the money they used to spend on the gaming side. And let’s be candid. The last $25 billion or $30 billion spent here didn’t return much to the investors. It’s been a rough five years.

“The biggest thing Vegas has going for it is its uniqueness. We’re the entertainment capital, after all. But it’s going to be a slow recovery to where we were five years ago. Room rates have not spiked like they have in the rest of the country. As they return, EBITDA is going to return. Non-gaming is going to be the catalyst in the future.”

Adelson is mounting a campaign against the spread of legalized online gaming in the U.S. While Goldstein says his boss has some moral opposition to the industry, he believes there’s a sound business reason to oppose it as well.

“What worries me about it is twofold,” he says. “First, the cost of entry is incredibly small, which means anyone can get into it. That shows me it is of limited value. Secondly, once you’re in it, it’s all about marketing dollars. The reinvestment becomes larger and larger. The customers have no loyalty. There’s no bricks and sticks that attract them.

“We thought that brands had real value online. But the more I look at it, the more I question that. Once a customer gets online, he looks for the best deal, so the deal becomes the driver. If that’s the case, the margins erode quickly. That’s the biggest fear for me, from a business perspective.”