Betting on Baseball in Vegas

It was the last month of 1941 and the St. Louis Browns were about to do something that hadn’t been done in decades: relocate a Major League Baseball franchise.

You see, the Browns competed in St. Louis with the mighty Cardinals, one of the most powerful franchises in the league. Not only couldn’t they match the talent that the Cardinals consistently produced, but they certainly couldn’t keep pace with attendance. The Browns’ annual attendance was among the worst in the American League.

But where to go? How about Los Angeles, the fastest-growing city on the West Coast? This was at a time when every other franchise in baseball was located east of the Mississippi River, so moving to L.A. would mean lots of travel and territory considerations, as well as a change of mindset. After all these issues were sorted out, a press conference was scheduled for… December 8, 1941.

Well, we all know what happened the day before. The start of World War II canceled the move to L.A. It was another dozen years before the Browns were able to escape St. Louis, but this time to Baltimore, where they became the Orioles.

Westward expansion didn’t begin until 1958, when the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles and the New York Giants headed to San Francisco.

In the meantime, there has been major league expansion and half a dozen relocations. But nothing has quite rivaled the move of the Oakland Athletics to Las Vegas, now scheduled for 2028. No team has ever taken up residence in yet another city prior to the move to their new home.

A’s Journey

The A’s were actually the second team to move after the Browns when they beat it out of Philadelphia, where they had won five world championships but always played second fiddle to the Phillies. The franchise relocated to Kansas City in 1955, becoming the first MLB team west of the Mississippi. The A’s were later purchased by maverick baseball owner Charley O. Finley, who found another city willing to build him a larger stadium in a bigger market and moved his team to Oakland.

The A’s thrived in Oakland, winning three consecutive World Series from 1972 to 1974 and again in 1989. But as the ownership of the franchise shifted several times, the team struggled. When John Fisher, scion of the family that founded the Gap clothing stores, took over in 2005, things began to look up. He hired Sandy Alderson, an experienced general manager, who in turn hired Billy Beane, a former player who brought serious analytics into the game.

The A’s thrived in Oakland, winning three consecutive World Series from 1972 to 1974 and again in 1989. But as the ownership of the franchise shifted several times, the team struggled. When John Fisher, scion of the family that founded the Gap clothing stores, took over in 2005, things began to look up. He hired Sandy Alderson, an experienced general manager, who in turn hired Billy Beane, a former player who brought serious analytics into the game.

When Brad Pitt played Beane in the movie Moneyball, the A’s and Beane became famous. The team won division championships in 2011 and 2012, but that’s when the latest slide began.

Attendance dropped as the quality of baseball declined after Fisher began to sell off the stars that Beane had produced, confident that Beane could simply create others.

Meanwhile, Fisher began lobbying for a new stadium, exploring options in various locations in Northern California. The most favorable option, the Howard Terminal, a waterfront shipping yard in Oakland, would have been a multibillion-dollar multi-use project. By that time, however, relations with city officials had soured and the deal disintegrated.

Las Vegas Bound

Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred then allowed the A’s to explore relocation, and Las Vegas came to call. The Nevada gambling mecca had previously poached Oakland’s NFL football team, the Raiders, so the blueprint was already set.

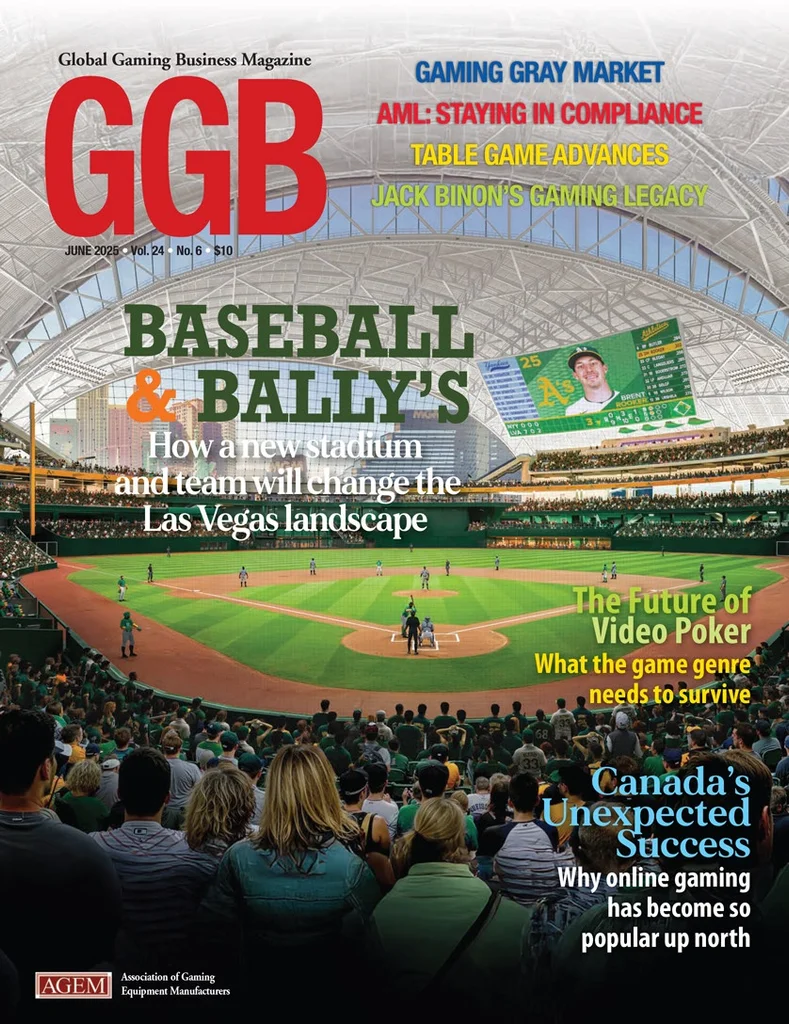

Several locations near the Las Vegas Strip were considered but discarded when the gaming real estate investment trust that owned the land the Tropicana was on, and Bally’s Corporation, the operator of the Tropicana, decided to contribute 9 acres of the 35-acre site for the stadium once the Trop was demolished in late 2024.

Clark County voted to dedicate $380 million in public funds to build the A’s stadium, due to be completed in 2028. But there was a problem. The A’s lease on the Oakland Coliseum ended in 2024, and the city wanted $90 million annually to allow the A’s to stay until the Vegas stadium is completed.

Fisher’s options were limited. Stay in Northern California and play in a minor-league stadium where he was guaranteed a $70 million TV contract, or come to Vegas to do the same—but get substantially less than that figure for a Nevada TV contract.

Fisher chose the money, and this year, the Athletics—just the Athletics, no city designation—are playing at the 11,000-seat Sutter Health Park in West Sacramento.

So why—other than the money—would Fisher opt for an unrelated city rather than come to Las Vegas immediately to build his fan base?

Steven Hill is president and CEO of the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority and also the chairman of the Las Vegas Stadium Authority. He believes that, in addition to the TV revenue, Fisher wants to make a grand entrance when the A’s arrive in Las Vegas.

“I think a bigger reason—and we talked about this—you take the splash out of them moving to Las Vegas” if they were to arrive now, he says. “If they move here in a smaller way—only 10,000 seats—you lose the PDA moment of them coming in 2028 to this great stadium and it being the first time that they’re in Vegas.”

Financing Follies

Although Fisher’s family is worth several billion dollars, there are still doubts about whether he has the wherewithal to finance the balance of the $1.75 billion stadium cost. But Hill says there is no reason to doubt Fisher, and the Stadium Authority has been assured via documents presented by Fisher that the money is there.

“We worked through the agreements on the Stadium Authority with them,” Hill says, “and it was a pretty straightforward process. It wasn’t simple, because it was a four-party agreement, but we got all that done on time. We know there has been a lot of chatter around this, but it has moved forward the way we have all said it would move forward, and that will continue. I don’t have any concern that won’t be the case.”

“We worked through the agreements on the Stadium Authority with them,” Hill says, “and it was a pretty straightforward process. It wasn’t simple, because it was a four-party agreement, but we got all that done on time. We know there has been a lot of chatter around this, but it has moved forward the way we have all said it would move forward, and that will continue. I don’t have any concern that won’t be the case.”

Fisher is still looking for investors—he floated a price of $500 million for 25 percent of the team, but since the team is objectively valued at around $1 billion, that proposal went nowhere. That doesn’t matter, according to Sandy Dean, an A’s spokesman quoted in an interview with the Nevada Independent.

“The Fisher family can get the stadium built regardless of any possible investors,” Dean said. “We’ve always thought it would be good for us to become more enmeshed in the Las Vegas market by having some local folks invest in the team.”

Groundbreaking for the stadium is set for sometime in June.

Hill references the success of Allegiant Stadium, the home of the Raiders. Also built with some public contributions, its price ballooned from $1.4 billion to $1.9 billion during construction. But even at that price, Allegiant has been a huge success for Las Vegas. It not only hosts all home Raiders games but has been used for the 2024 Super Bowl, international soccer matches and many concerts by the biggest superstars. It also will welcome college basketball’s Final Four in 2028.

Hill sees the two stadiums as being symbiotic in attracting even more events.

“For the most part, the baseball stadium will be available when Allegiant Stadium is in use,” he says. “Allegiant will be open through the summers, and the baseball park will then be used after the baseball season ends. They’re not the exact same size, but we’ll have pretty decent-sized venues available year round because we have those two facilities. So we we’re pretty excited about that.”

Bally’s Plans

The four parties involved that Hill referred to are Clark County, the A’s, property owner Gaming & Leisure Properties, Inc., and Bally’s, the operator of the casino complex that is to be announced soon.

Bally’s plans for a casino resort surrounding the stadium have changed, according to Soo Kim, chairman of Bally’s Corp. When the deal was first announced, Kim envisioned a community coming together.

“By giving the A’s the land, we’re showing our belief in the value of having this stadium,” Kim told the Independent. “I have good relations with a lot of the community groups in Vegas, which we’ve been building. We’re going to have a very strong community benefits package that makes it clear that everyone is benefiting from this.”

Though a rendering of a 5,000-room casino resort was first released, Kim tells GGB that another concept has been discussed.

“This is going to be almost like more of an RED (retail, entertainment, dining) build than a hotel-casino build,” he says. “We’ll have a casino and a hotel for sure, but I think that an RED development is the most obvious opportunity, because every stadium in America has these large RED, mixed-use developments around the stadium.”

Atlanta’s baseball stadium is a perfect example. The team moved from a stadium in downtown Atlanta to Truist Park and The Battery, a mixed-use development encompassing One Ballpark Center. St. Louis and Philadelphia have also developed RED districts outside Busch Stadium and Citizens Bank Park, and several other major league teams have joined this trend.

“And they’re in cities where you can’t have a casino,” Kim says. “We can add a casino and a hotel, on top of that. And it’s not only the games, but also the concerts and other events which capture that energy by creating this retail corridor.”

Baseball Village

Kim says he’s looking for a retail partner, but the most obvious one doesn’t work. The Cordish Companies have developed several of these destinations, most notably in Philadelphia, Dallas and St. Louis. But it’s unlikely Bally’s would work with the developer, because Cordish filed legal action seeking to block a Bally’s mini-casino near State College, Pennsylvania, a project that now includes neither company.

Kim says the Las Vegas development would be a walkable plaza adjacent to the stadium that would be elevated with the logistics located down below—parking, access to the retail, restaurants and hotels. While Bally’s would certainly have a small hotel-casino, he doesn’t rule out the possibility of a second casino project within the development.

Kim likens the development to BLVD, a new project on the Las Vegas Strip just a block away, which is an RED project that replaces the former Hawaiian Market.

The BLVD website describes it as “a high-profile, high-impact, all-day destination on the Strip offering a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to connect with consumers from across the world.”

The BLVD website describes it as “a high-profile, high-impact, all-day destination on the Strip offering a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to connect with consumers from across the world.”

As for the timeline of the development of the Bally’s RED district, Kim says it’s still up in the air.

“We have a few months to decide,” he says, “but if we miss that window, we’d have to give them notice a year in advance, and then we can go afterwards. Frankly, we can still get it done around the same time that they do, but it’s just a lot easier to decide now. Anyway, we’re working really hard. It feels pretty good.”

Kim says his company has contacted MGM Resorts, whose hotel casinos are on the adjacent three corners, about working together.

“We love the fact that we’re building on a corner that has 11,000 hotel rooms, 11,000 parking spots, and we will add our attractions to that,” he says. “We think it’ll just drive even more traffic to the area. We have spoken to MGM about potentially rebuilding the pedestrian bridges, so that it connects the entire area and reinvigorates the south end of the Strip. We’ve been having a good dialogue with MGM, actually.”

For Hill, the investments by some of the biggest sports stars in Las Vegas franchises are a good thing.

“It’s a great investment,” he says. “It’s fun to be a part of. There’s such possibility because you’re in Las Vegas, and we think it’s great. It’s starting to create that critical mass where some great things can happen and then others want to be a part of it.

“Whether it’s Tom Brady or LeBron James, or Shaquille O’Neal or Magic Johnson, they’re all a part of what’s happening in Las Vegas in different ways, and it just builds all by itself. And I think they see that opportunity and so do we, so we welcome it.”